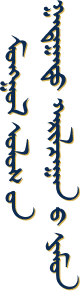

By Chanrav Burenbayar

Archery is as ancient as the history of Mongolia. In ancient days bows and arrows were primarily used for hunting animals for food, and protecting the tribe from outside threats. Over the centuries, the uses of archery changed and the tradition of archery was passed down to become one of the most important elements of the sport competitions held within the National Naadam Games.ÂÂÂÂ Historical sources cite a couple of instances when bows and arrows were almost outlawed, threatening the disruption of this important cultural tradition of Mongolians. Bows and arrows were outlawed and confiscated during the Manchu-Qing Empire rule in Mongolia; and according to contemporary archery historians, during the years of political persecution in the 1930s as it was considered a “weapon of destruction.”

Whatever the historical circumstances, the tradition of archery continued and developed. Tomorkhuu Batmonkh, Director of the Eriin Gurvan Naadam Company specializing in the Mongolian bow and arrow can be given special mention for his contribution to modern Mongolian archery.

Formerly a professor of geography at the Mongolian State Teacher’s Training University (today’s Mongolia’s Education University), Batmonkh started his business of making traditional Mongolian bows and arrows some 20 years ago. He hails from Sharag Soum in Gobi Altai Aimag, and moved to Ulaanbaatar in 1971 as a student to settle down and raise a family.history & culture asked how a geography teacher got into the business of -making, Batmonkh said, “I am an archer myself so it was natural to understand what archery meant to Mongolians. I started researching the art of bow-making and also wrote two books about archery and bow-making traditions.”

But how did he start making bows and arrows, of which he is perhaps one of the top professionals in the country? “I learned the art of bow-making from senior bow-makers as there were many of them, but not many continued in the tradition”, said Batmonkh; who added that he does not have a tradition of bow-making in his family, but some relatives among his former two generations were talented craftsmen. “Perhaps this kind of talent in our blood helped me become a bow-maker” he said, and continued that “bowmaking is precision work, demanding patience and a little bit of talent. Even the excessive use of the glue or a slight disfigurement of the horn used in the composite bow could cause the archer to miss the target.”

As soon as you enter his 3-room apartment in the Bayangol District of Ulaanbaatar, his love for this profession is evident. One of his bedrooms is turned into a kind of warehouse where new bows are kept, and his living room is his workshop with sinews, glue, arrows, bird feathers, arrowheads, readymade bows, tools, and implements everywhere. A special place in the room had been assigned to his collection of bows and arrows used by ancient Hun- nu, Mongolian soldiers hundreds of years ago, as well as Manchurian, Japanese, Korean, English, Buryat, Korean and even Red Indian bows and arrows. But among them, the most treasured is a bow and arrow, especially crafted by Batmonkh, on which was placed a decree by Mongolia’s President in 2002 who announced the promoting and developing of national archery, initiated by Batmonkh. His wife joined in proudly, saying that “my husband has devoted himself to promoting national archery. Today, national archery has become a national sport and archery competitions are held all across all 21 aimags of Mongolia.”

In the 1980s only about 30 to 40 men and boys were taking part in the Naadam archery competition. Some 70% of the archers were old people and only 30% were young people, whereas today 400-500 archers compete in the Naadam Games and more than 70% of the participants are young people. “This is how far we have come in promoting national archery,” said Batmonkh.

There are basically three kinds of archery in Mongolia – Khalkha, Buryat and Uriankai, given the specifics of the lifestyle and pattern of different Mongolian tribes.

In Uriankhai archery competition, 30 arrows are shot at the target, balls weaved of camel hide from a distance of 40 meters. The winning archer not only hits the target most, but his shots roll over the ball targets to a small mound of soil erected behind the piled target of leather balls. Uriankhai arrows are 90-100 cm long, 1.1-1.3 cm in diameter and weigh 50-60 grams.

In Buryat archery, both men and women compete and shoot at cylindrical targets made of weaved camel hide from a distance of 30 meters (women) and 45 meters (men) and let loose a total of 64 arrows. The Buryat arrows are 140-150 centimeters long.

While national or Khalkha archery is the standard and targets are shot at a distance of 65 meters for women, and 75 meters for men. Khalkha arrows, as compared to Buryat arrows, have tips made of animal horns and the fletching is made from bird feathers.

In the 1960’s, women archers started competing in the Naadam which was a “significant development in national archery” that added dimension to making archery a truly national sport, said Batmonkh. He also talked about what materials are used, how the bows and arrows are made and how they differ from bows used by other peoples around the world as well as their similarities.

Birch wood is used for making a bow. It takes one year to make a bow. The birch wood is first cut, glued and shaped into a bow and kept to dry for one year. One of Batmonkh’s bedrooms was turned into a room for drying the bows and each one of them had dates of when they were put up to dry.

Mongolian bows are composite bows. The core is bamboo, with the horn on the belly (facing the archer) and sinew on the back, bound together with animal glue, very different from “self” bows. The advantage of composite bows is the combination of small size with high power. They are therefore more convenient than “self” bows when the archer is mobile, as from horseback.

There is an inscription on a stone stele was found near Nerchinsk in Siberia: “While Chinggis (Genghis) Khan was holding an assembly of Mongolian dignitaries, after his conquest of Sar- tuul (Khwarezm), Yesungge (the son of Chinggis Khan’s brother) shot a target from 335 alds (536 m).”

The bows used today in sports have not changed much from those of the ancestors, according to Batmonkh. “However, they had their development stages too”, he said, showing me a replica of a Hunnu bow designed after a bow found in a Hunnu grave. The bows became composite, with sinews added to increase the draw weight, the bending section becoming smaller, etc.

As the country progresses, and with the growing number of people going in for archery and other sports, there are many more craftsmen producing bows and arrows.

Besides the growing number of archers and the growing interest in national archery, foreigners are also interested to learn more about Mongolian archery traditions and how the bows and arrows are made, according to Bat- monkh. Lately, he has been receiving orders for Mongolian bows and arrows from overseas.

“The most important thing is trust. A foreigner sends money and asks for a bow giving its weight, and we deliver it per specifications of the order” said Batmonkh. He gave me his business card with his contact information, should anyone be interested in not only buying bows and arrows: www,mongolianarchery.com; email: info@mongolianarchery.com.

Equally important is the fact that his son and daughter, and even his grandchildren, know and are learning Batmonkh’s trade and art, a sign that this age-old tradition of crafting bows and arrows will continue. At the end of our meeting I wanted to take his picture. He said “wait a moment” and came back dressed in his best del and posed for the camera, — a proud Mongolian craftsmen, proud of traditional customs and culture, and proud that traditional archery has become a national sport.